How to Build an AI-Ready Finance Stack (Even Without a Data Team)

TL;DR

The Thesis: You do not need a team of data scientists to build an autonomous finance stack; you need rigorous data engineering that decouples "reasoning" (LLMs), "calculation" (deterministic code), and "definition" (metric layers).

- The Trap: Treating finance as a machine learning problem. LLMs are probabilistic engines that fail at precise arithmetic and often view "Profit" and "Loss" as semantically identical. Trust collapses when you ask a probabilistic model to perform deterministic accounting.

- The Fix: A "Router-Solver" Architecture backed by a Semantic Layer. Use the LLM only to understand intent and categorise ambiguity. Then, route the query to deterministic tools (SQL/Python) that execute hard-coded financial logic defined in a single source of truth (like dbt).

- The Exception: Classification, not Calculation. While LLMs fail at maths, they excel at categorisation. Use them to map "Starbucks" to "Meals & Entertainment" (GL Coding), but never to sum the total of those meals.

- The Outcome: A system capable of answering CFO level questions with >95% accuracy, auditable lineage, and zero reliance on "black box" model training. Success is measured not by how well the model chats, but by passing a "Golden Set" of verified financial queries.

1. Introduction

The modern finance function is trapped in a dilemma, caught between archaic manual workflows and the seductive, often misleading promises of futurists.

On one side, there is the "Spreadsheet Wall." This is the inevitable breaking point where manual reconciliation, cell-based forecasting, and static reporting collapse under the weight of operational complexity. For decades, the solution to more complexity was simply "more spreadsheets." But in a modern stack where data lives in fragmented silos like Stripe, Salesforce, Gusto, and Xero the spreadsheet is no longer a tool; it is a bottleneck. The FP&A cycle becomes a monthly fire drill of downloading CSVs, fixing broken VLOOKUPs, and praying that "Financial_Model_v3_FINAL.xlsx" is actually the final version. The result is a finance team that looks backward at stale data rather than forward at strategic opportunities.

On the other side, there is the Hype of AI. Every week, a new demo promises a "Digital CFO" that can ingest your bank feeds, predict your runway, and automate your board deck. It looks magical in a 30-second Twitter video. You drag a PDF into a window, ask "How much did we spend on software?" and it spits out a number. It feels like the solution to the Spreadsheet Wall. But for finance leaders, this magic often dissolves upon the first real audit. The answers are plausible but frequently incorrect, hallucinating line items or misinterpreting accounting periods.

Most finance leaders, recognising this gap, assume the solution lies in hiring. They believe bridging this gap requires a massive investment in a specialised Data Team hiring PhDs to train proprietary models and fine-tune neural networks on their private data. They view "Financial AI" as a machine learning problem, thinking they need to teach a computer to "think" like a CFO.

This is a fundamental misconception.

Financial data is not a fuzzy pattern to be "learned" like an image, a poem, or a translation. It does not require the probabilistic intuition of a neural network to decide if a transaction is revenue or expense. Finance is a set of rigid accounting identities governed by strict rules. Profit is not a "prediction"; it is a calculation. Runway is not a "vibe"; it is a formula.

When you hire data scientists to solve a finance problem, they bring probabilistic tools to a deterministic domain. They try to train models to predict numbers that should simply be queried. The result is an expensive R&D project that produces a "smart" chatbot that can't reliably balance a ledger.

Building an AI-ready stack is not a research project; it is a systems engineering challenge. It is about plumbing, not poetry. It requires building a bridge between the reasoning capabilities of modern LLMs and the computational reliability of databases. The goal is not to replace the CFO with a robot, but to give the CFO a tool that scales their logic without scaling their headcount.

2. The Core Problem: The "Data Science" Trap

The status quo approach to Financial AI-the one currently being pitched by thousands of startups and implemented in countless internal hackathons often follows a predictable, flawed pattern. It starts with the "Dump and Pray" method: engineers take a massive collection of unstructured financial artifacts like PDF invoices, CSV bank exports, earnings call transcripts, and board decks and dump them into a vector database. They then slap a chat interface on top and let a Large Language Model (LLM) "chat" with the documents.

This architecture is technically known as RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation). In the broader tech world, RAG is a revolution. It allows an AI to read your company handbook and answer, "What is our paternity leave policy?" with incredible accuracy. It works because policies are semantic; they are made of words, intent, and nuance.

However, when you apply this same architecture to finance, it is disastrous.

The problem isn't the technology itself; it's the domain mismatch. Finance is not a text retrieval problem; it is a structured logic problem. When you ask, "What was our Q3 churn?", you are not looking for a paragraph of text that mentions the word "churn." You are looking for a precise mathematical aggregation of subscription events within a specific date range, filtered by customer type. A vector database, which retrieves information based on "fuzzy" similarity, is fundamentally ill-equipped for this precision.

The "Hidden Tax": Trust Erosion The most dangerous consequence of this approach is not technical; it is cultural. We call this the "hidden tax" of trust erosion.

In creative fields, AI hallucination is a feature; it sparks creativity. In finance, hallucination is a fatal error. If a "Digital CFO" bot hallucinates a burn rate of $200k when the real number is $350k, or if it confidently retrieves last quarter’s revenue to answer this quarter’s query, the damage is immediate and often permanent.

Finance teams operate on a "zero-defect" culture. The moment a tool provides a single factually incorrect number, the CFO will lose faith in the entire system. They will not ask, "Why did the model drift?" They will simply close the browser tab and revert to Excel. The tool shifts from being a "productivity multiplier" to a "liability," and the project dies.

The Opportunity Cost of Verification This leads to a massive, invisible opportunity cost. Instead of analyzing strategy or modelling future scenarios, highly paid financial analysts find themselves forced into the role of "AI Auditors." They spend 40-60% of their time manually verifying the numbers generated by the "intelligent" system.

Consider the irony: we build AI to save time, but because the "Chat with Data" approach is a non-deterministic "black box," the human operator must re-calculate every output to ensure safety. It is often faster to simply calculate the number manually than to prompt the AI, wait for the answer, audit the lineage, find the hallucination, and correct it. If the AI cannot be blindly trusted to perform basic arithmetic, it is not an asset, it is a distracted intern that requires constant supervision.

3. Failure Modes: Why "Chatting with Data" Breaks

When we initially attempted to feed raw financial data to an LLM using standard vector search, we encountered catastrophic failure modes. These are not theoretical problems. They are observable, repeatable breakages that happen whenever you build a naive AI finance stack.

We identified five specific ways the "Chat with Data" model collapses in a production finance environment.

- Semantic Blindness In the world of vector databases, text is converted into numbers (embeddings) based on meaning. The problem is that the words "Profit" and "Loss" are semantically very close. They appear in identical contexts, usually next to currency symbols or quarterly dates. A naive search for "high loss divisions" will often retrieve documents about "high profit divisions" because the embeddings overlap significantly. The AI retrieves the exact opposite of what you asked for because it matches the pattern of the sentence rather than the specific financial polarity.

- The Tokenization Gap We tend to forget that LLMs do not see numbers; they see tokens. To a model like GPT-4, the number 1000 might be a single token, while 1,000 is read as two separate tokens.This inconsistency makes LLMs notoriously bad at arithmetic. It is like asking a calculator to do math using only poetry. The model tries to predict the next digit based on what usually follows, rather than calculating the value. This results in calculation errors that look plausible on the surface but are factually wrong.

- Magnitude Blindness A standard retrieval system struggles to distinguish between "Net Income of $10M" and "Net Income of $100M". It retrieves information based on text overlap, not numerical magnitude. If you ask for "largest expenses," the system might return a $500 software subscription simply because the invoice contained the word "expense" five times, while missing the $500,000 server bill that was described as "infrastructure cost."

- Temporal Hallucination Finance is deeply time-sensitive. A query like "Q3 Revenue" is meaningless without a year, yet documents often just say "Q3" in their headers. If document metadata isn't strictly enforced, the AI will happily return data from Q3 of the previous year because "Q3 2023" and "Q3 2024" look semantically identical to the retrieval engine.

- The Summation Trap This is perhaps the most common failure. Asking an LLM to "calculate MRR" from a list of raw invoices often triggers a simple SUM() operation. The model sees a column of numbers and adds them up. It fails to apply the necessary business logic, such as amortizing annual plans over twelve months or excluding failed payments. The result is a wildly inflated revenue figure that the user might blindly trust because the AI "read" the documents.

4. Why It Fails: The Determinism Mismatch

The root cause of these failures is fundamental. It is not about bad prompting or insufficient data. It is a collision between two opposing systems of logic: Finance is deterministic, while LLMs are probabilistic.

To understand why this breaks, you have to look at what an LLM actually is. It is a massive next-token prediction engine. When you ask ChatGPT a question, it is not "thinking" in the human sense. It is calculating the statistical likelihood of which word should come next based on billions of examples it has seen before. It is essentially "autocomplete" on steroids.

Financial reporting, however, requires absolute exactness.

In finance, truth is binary. Profit equals Revenue minus Cost. There is no "probability" involved here; it is a hard rule. If the answer is off by a single cent, it is wrong. There is no partial credit. When you ask a probabilistic model to perform this deterministic task, you are asking it to guess the answer based on patterns it has seen in training data, rather than calculating the answer based on the inputs in front of it.

This is why trying to teach an LLM to "learn" arithmetic or accounting rules via fine-tuning is so inefficient and error-prone. You are trying to train a pattern-matching engine to simulate a logic engine. It is like trying to teach a parrot to do algebra. It might memorize "2 + 2 = 4" because it has heard it often enough, but ask it "2.1 + 2.1" and it might confidently squawk "Five" because that sounds right.

The failure lies in a simple category error: asking the reasoning engine (the AI) to do the job of the calculation engine (the Database or Code). You don't need a model to predict your MRR based on a "vibe." You need a calculator to compute it based on the ledger. Until you separate these two functions, your finance stack will remain an unreliable toy.

5. The Better Model: Agentic RAG with Function Calling

The solution to the determinism mismatch is to stop asking the LLM to do the math. We need to fundamentally demote the LLM from being the "doer" to being the "planner."

In this better model, we treat the LLM as an orchestrator that routes questions to the correct tools. We call this the "Router-Solver" Architecture. It typically yields accuracy rates exceeding 95% because the mathematical heavy lifting is handled by deterministic code, not probabilistic tokens.

The "Router-Solver" Architecture This architecture strictly bifurcates responsibilities into two distinct layers:

This architecture bifurcates responsibilities:

- The Reasoning Layer (The Brain): This is the LLM (e.g., GPT-4o, Claude 3.5 Sonnet). Its only job is to handle the user's natural language query, understand the intent, and extract the necessary parameters. It decides what needs to be done, but it never actually does the calculation.

- The Tool Layer (The Hands): This layer consists of deterministic scripts, typically written in Python or SQL, that execute specific financial logic. These are hard-coded functions that cannot hallucinate because they follow rigid programming rules.

5 Principles of the Fix To build this effectively, you must adhere to five core engineering principles:

- Principle 1: Code is the Calculator. Never let an LLM perform arithmetic. If a user asks for "Average Burn," the LLM should not look at data and try to average it. Instead, it should generate a SQL query or call a specific Python function like calculate_burn(). The AI writes the code (or calls the function), and the machine executes it.

- Principle 2: Structured Data Stays Structured. Do not fall into the trap of turning your SQL rows into text chunks for a vector database. This destroys the relational integrity of your data. Keep your financial data in a structured warehouse (like Snowflake or Postgres) and give the agent a tool to query it directly. The agent should come to the data; the data should not be degraded to fit the agent.

- Principle 3: Define the Logic Once. The definition of a metric like "Gross Margin" should live in a single "Single Source of Truth," such as a SQL view or a dbt model. It should never live in the prompt of an LLM. If you put logic in the prompt, you have to update it everywhere. If you put it in the code, the AI simply queries this trusted source.

- Principle 4: Disambiguate with Routing. Not every query requires a database. Use a router to decide the nature of the request. If the query is qualitative ("What is our travel policy?"), route it to a traditional RAG system. If it is quantitative ("What is our travel spend?"), route it to a SQL Agent. This ensures the right tool is used for the right job.

- Principle 5: Continuous Evaluation. Accuracy isn't achieved on day one. You must implement a feedback loop where the AI's output is constantly compared against a "Golden Set" of verified answers. This allows you to refine the tool definitions and prompts based on actual performance rather than intuition.

6. Illustrative Example: Calculating MRR from Stripe

Let's look at a specific, real-world scenario that trips up almost every basic AI finance tool: "What is our current Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR)?"

The Naive (Failed) Approach: In a standard RAG setup, a user uploads a CSV export of Stripe invoices to a chatbot and asks the question.

- Process: The LLM scans the document, identifies a column labelled "Amount," and attempts to sum the values. It sees rows of data and applies a simple addition operation.

- Failure: The model lacks context. It sums the full value of annual plans (e.g., $12,000) as if they were monthly payments, massively inflating the number. It includes "failed" or "refunded" transactions because the text "Amount" appears next to them, regardless of the status column.

- Result: The AI confidently reports, "Our current MRR is $500,000." This number is wildly incorrect, but it looks plausible enough that a busy executive might believe it.

The AI-Ready (Engineered) Approach: In the Router-Solver model, we do not feed raw data to the LLM. Instead, we build a specific tool called get_stripe_mrr.

- Input: The user asks, "What is our MRR?"

- Router: The LLM analyzes the request and identifies the intent as "Metric Calculation." It knows it cannot answer this itself.

- Agent: The orchestrator triggers the get_stripe_mrr() tool.

- Deterministic Logic (The "Black Box" is Code, not AI): A Python or SQL script executes strictly defined business logic.

- It filters the database for status = 'paid'.

- It identifies annual plans and normalizes them (divides the amount by 12).

- It subtracts any discounts, refunds, or credits.

- Output: The script calculates the result and returns a raw float: 42150.50.

- Response: The LLM receives this exact number. Its only job is to format it into a sentence. It responds: "Our current MRR is $42,150.50."

The Result: The LLM didn't do the math. It didn't guess the logic. It simply delivered the message. By moving the logic from the prompt (probabilistic) to the script (deterministic), we achieved 100% accuracy on the calculation while still keeping the conversational interface.

7. What This Unlocks

By shifting your architecture from "Generative" (asking an AI to create answers) to "Agentic" (asking an AI to use tools), you unlock capabilities that were previously impossible without a massive human team. You move from a system that guesses to a system that works.

- Radical Auditability (The "Receipt") In a standard LLM chat, if the model tells you revenue is $10M, and you ask "Why?", it might hallucinate a justification. In an Agentic system, every number comes with a "trace." You can inspect the logs to see exactly which tool was called, which SQL query was executed, and which raw data rows were processed. The AI doesn't just give you an answer; it gives you a receipt. If a number looks wrong, you don't debug the neural network; you debug the SQL query. This transparency is the difference between a toy and a tool.

- True CFO-Level Reasoning Static dashboards tell you what happened. An Agentic Finance Stack can tell you why. You can ask complex, multi-layered questions like, "Why did our Gross Margin drop in Q3?".

- The agent first retrieves the Q3 margin.

- It notices the variance against Q2.

- It drills down into cost categories (Cost of Goods Sold).

- It identifies that "Server Costs" increased by 40% and references the exact AWS invoice line items that caused the spike. This is the holy grail of FP&A: automated variance analysis that actually identifies the root cause.

- The "Zero-Training" Advantage There is a pervasive myth that you need to "train" a model on your data. This is false. With the Router-Solver approach, you do not need to fine-tune a neural network or burn GPU hours teaching a model what an invoice looks like. You simply need to connect your APIs like Stripe, Xero, QuickBooks, Zoho Books to standard calculation tools. The "intelligence" of off-the-shelf models like GPT-4 is already sufficient to understand English; your only job is to provide the tools. This means you can deploy in days, not months.

- The Trust Economy The ultimate unlock is psychological. When the AI's output matches the general ledger exactly down to the cent. The relationship between the finance team and the technology changes. They stop treating it like a "beta test" or a curiosity. They stop debugging the AI and start using it for strategy. Trust is the currency of finance, and deterministic tools are the only way to earn it.

8. The "Semantic Layer" (The Missing Link)

If "Code is the Calculator," then the Semantic Layer is the dictionary.

One of the biggest hurdles in building a finance bot is that database schemas are rarely self-explanatory. A column named amount_usd in a transactions table tells you nothing about the business context. Is that revenue? Is it a refund? Is it tax-inclusive?

If you give an AI direct access to your raw database tables, it will guess. It might assume SUM(amount_usd) is Revenue. But in your business, "Revenue" might actually be defined as: SUM(amount_usd) WHERE status = 'complete' AND type != 'tax' - SUM(refunds).

You cannot expect the LLM to derive this nuance from column names alone.

The Fix: You must implement a Semantic Layer (using tools like dbt, Cube, or Looker). This layer acts as a translator between raw data and business concepts.

- You define "Revenue," "Gross Margin," and "Churn" once in code.

- The AI does not query the raw tables; it queries these pre-defined metrics.

- When the user asks for "Revenue," the AI requests the Revenue metric from the semantic layer, which executes the complex SQL logic hidden underneath.

This ensures that the definition of "Profit" is consistent whether it appears in a board deck, a dashboard, or a chat window.

9. The Exception to the Rule: Classification, Not Calculation

Throughout this piece, we have argued that LLMs should not do math. However, there is one specific area in finance where LLMs are vastly superior to deterministic code: Classification.

Finance is full of messy, unstructured labels. A credit card statement might read SQ *POUR COFFEE 8832. A deterministic rule (Regex) needs to be constantly updated to know that this string means "Starbucks" and belongs in the "Meals & Entertainment" ledger.

The Strategy: Use the LLM for General Ledger (GL) Coding.

- Input: The raw transaction description (SQ *POUR COFFEE).

- Task: "Map this description to one of our Standard Chart of Accounts codes."

- Output: 6040 - Meals & Entertainment.

LLMs excel here because they understand semantic context. They know that "Uber," "Lyft," and "Yellow Cab" all conceptually map to "Travel," without you having to hard-code every variation. In this architecture, the AI cleans the data before it enters the calculation engine. It structures the chaos so the code can do the math.

10. The "Clarification Loop" (Handling Ambiguity)

In a conversation, humans are vague. A CFO might ask, "How is the burn looking?"

A naive bot will immediately try to answer. It might calculate "Gross Burn" (total expenses) when the CFO actually cares about "Net Burn" (expenses minus revenue). If the bot guesses wrong, it loses trust.

The Fix: Implement a Clarification State in your router.

- Step 1: The user asks a vague question.

- Step 2: The Router detects ambiguity. It recognises that "burn" could mean multiple things.

- Step 3: Instead of calling a calculation tool, the AI calls a clarify_intent tool.

- Step 4: The bot responds: "Do you mean Gross Burn (total spend) or Net Burn (spend minus revenue)?"

This simple loop prevents the "confidence trap," where an AI provides a confident but wrong answer to a vague question. It mimics a high-quality human analyst who would ask clarifying questions before running the numbers.

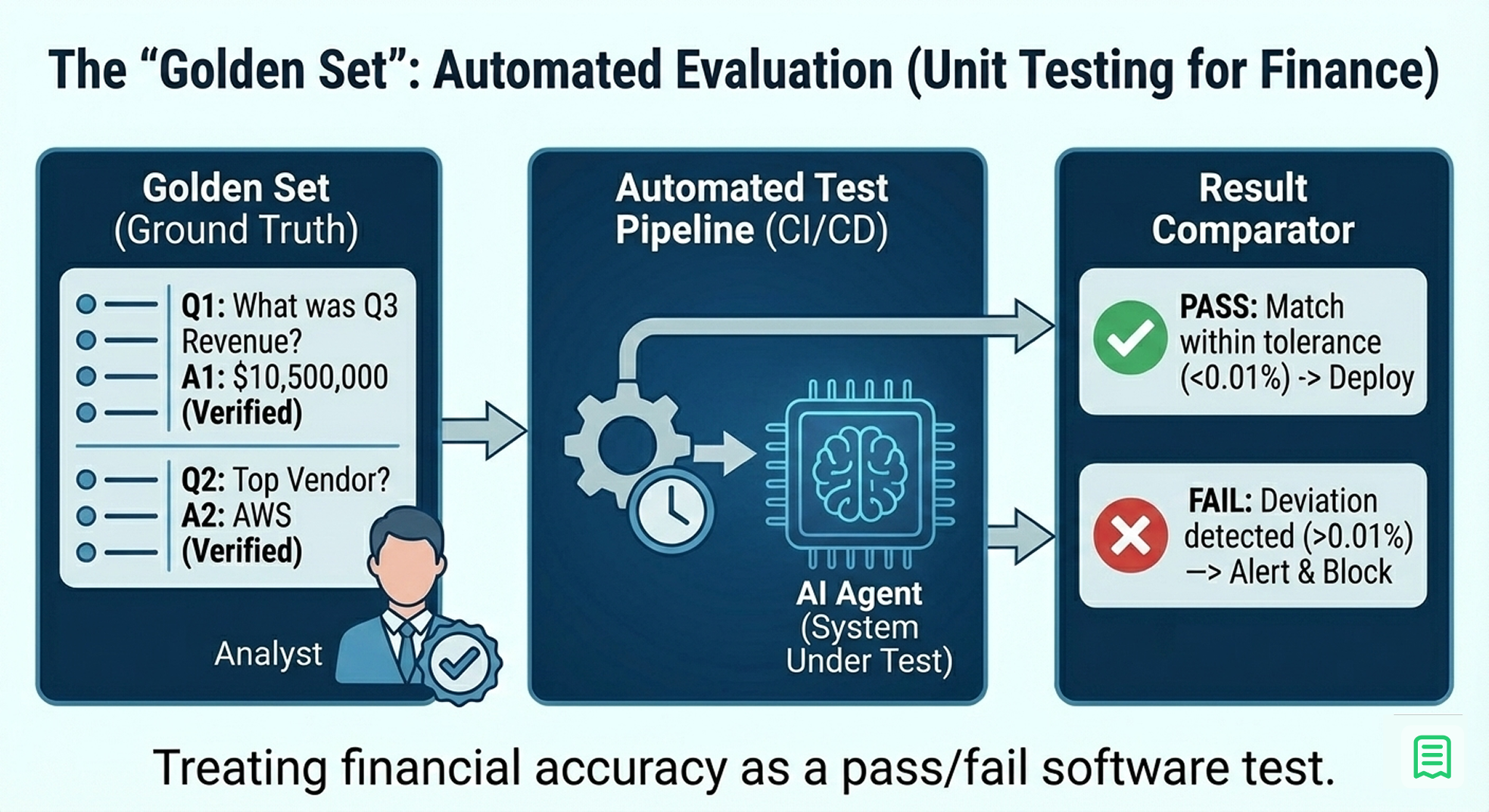

11. The "Golden Set" (Automated Evaluation)

How do you know if your finance stack is working? You cannot manually check every answer. The solution is to borrow a concept from software engineering: Unit Testing.

You must build a "Golden Set" , a dataset of questions with verified, hard-coded answers.

- Create the Set: Write down 50 common questions ("What was Q3 Revenue?", "Who is our top vendor?", "What is the current bank balance?").

- Verify the Truth: Have a human analyst manually calculate the correct answers using SQL or Excel and store them as the "Ground Truth."

- Automate the Test: Every time you update your prompt or code, run the AI against these 50 questions.

- Fail on Deviation: If the AI's answer deviates from the Ground Truth by more than 0.01%, the build fails.

This turns "accuracy" from a feeling into a metric. You can confidently say, "Our system is 98% accurate on the Golden Set," rather than "It feels pretty good."

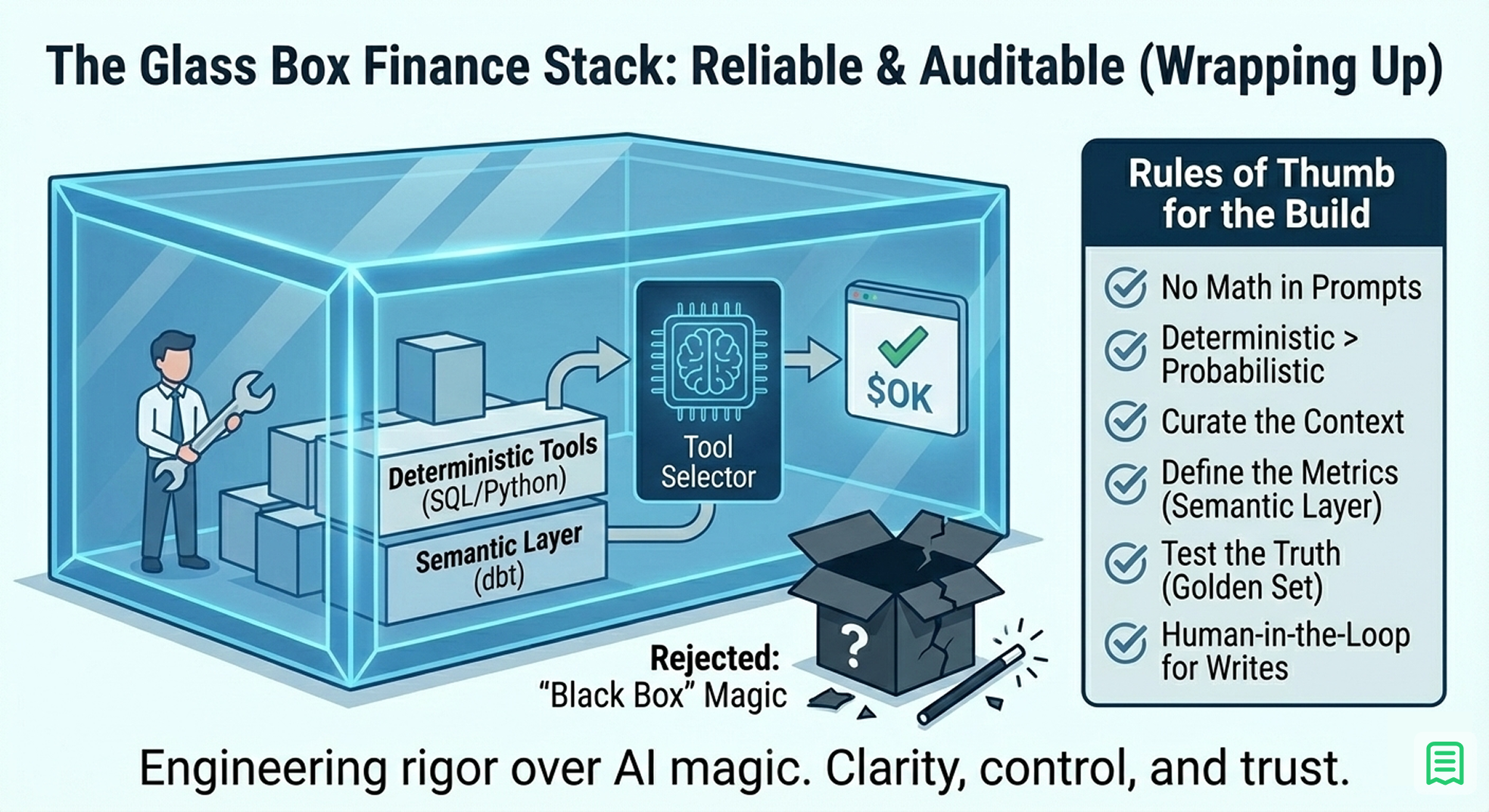

12. Wrapping Up

Building an AI-ready finance stack is not about hiring data scientists to build brains; it is about hiring engineers to build tools.

The "intelligence" of modern LLMs is already sufficient to understand what you need; your job is to give them the reliable tools to get it. The future of finance isn't a "magic box" that predicts the future; it is a "glass box" that clarifies the present auditable, transparent, and accurate.

Rules of Thumb for Your Build:

- No Math in Prompts: If it involves a +, -, *, or /, it belongs in code.

- Deterministic > Probabilistic: Always prefer a database query over a vector search for numbers.

- Curate the Context: Don't dump everything into the AI. Feed it only the schema it needs to call the right tools.

- Define the Metrics: Use a Semantic Layer to define "Revenue" once, so the AI doesn't have to guess.

- Test the Truth: Don't trust; verify. Build a Golden Set and run it regularly.

- Human-in-the-Loop for Writes: Never let the AI modify the database without human approval.